Handheld flashlight techniques are an essential skill for personal defense.

In the age of high-quality, dependable firearm-mounted lights, the handheld light remains an indispensable tool. In both police and armed civilian scenarios, it is common for the good guy to start the engagement without their pistol in hand; good guys are most often reactive to the threat.

As great as mounted lights are, they are often not the appropriate tool for the task at hand. If you are searching for a known bad guy or have other reasons to believe that there is an imminent threat, then a mounted light is the clear choice. However, the good guy is usually investigating something that falls below that imminent threshold, meaning that the search is happening with a handheld light and the firearm is holstered. This is where most professional training has let the shooter down.

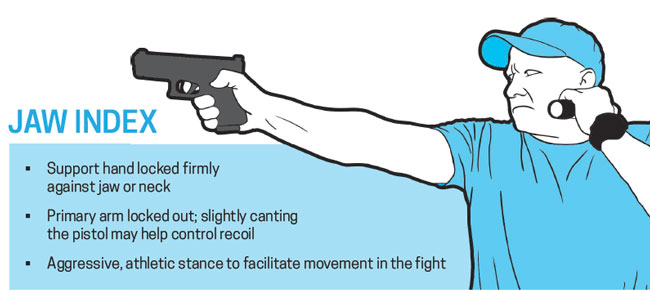

Jaw Index Technique

When I was taught the traditional Harries flashlight technique, it was with a structured, numbered draw count. This is done to ensure that the shooter doesn’t cover their support hand and flashlight with the muzzle of the gun. It’s a good place to start, but most training never progresses past that. That’s a huge problem because most of the time, that searching light will be in front of or above the shooter, not held tightly against the body. During real-life engagements, this means that the shooter is drawing from an unfamiliar position and can end up covering that support hand in a rush to get into the handheld technique of their choice. In force-on-force (FOF) scenarios, I have even seen shooters shoot themselves in the support hand. It also leads to sloppy, less effective techniques, contributing to many shooters’ poor low-light shooting. Fighting in low light is very different from structured, square-range shooting in low light, and this fact seems to be lost on many shooters and trainers.

Techniques

During the low-light package that is taught at the SureFire Institute, students are given instruction on multiple one-handed flashlight searching to shooting techniques. These include the old FBI technique and the neck or jaw index positions. The FBI technique requires the light to be held up and away from the body, ostensibly to give the bad guy a target to shoot at away from the good guy’s vitals. In the age of 1,000-lumen retina burners, this aspect of the technique may be questionable, but what is not questionable is that this is a great searching technique. It allows the searcher to angle the light and utilize the corona and spill to accomplish the bulk of the work while leaving the center hot spot off reflective surfaces. If something of interest is caught in the corona, then it’s easy and reflexive to place the hot spot on whatever you want to give some of those additional lumens.

Light is necessary to positively identify a target. Good handheld light techniques allow for the use of standard sights,